Archive for the ‘sql’ Category

MySQL Explain Plan

I finally got the magic trick to find the explain plan for a query in MySQL, but chagrined to find out that you can’t explain the cost or execution of INSERT, UPDATE or DELETE statements. This blog shows you how to get the execution and execution plan for a query and the error when you try to EXPLAIN DML (Data Manipulation Language) statements.

You can see the selection type, possible indexes, chosen index, et cetera:

EXPLAIN query; |

You can see the selection type, possible indexes, chosen index, et cetera plus the query execution plan with the magic EXTENDED key word:

EXPLAIN EXTENDED query; |

In some cases, you may need to type SHOW ERRORS to see the execution plan. There’s no way to format it natively, like Oracle, but there may be a tool out there.

If you try to explain a DML statement, you’ll get an error message like the following:

ERROR 1064 (42000): You have an error IN your SQL syntax; CHECK the manual that corresponds TO your MySQL server version FOR the RIGHT syntax TO USE near 'UPDATE city SET District = 'Funny'' at line 1 |

The last rule of thumb on query execution is that you should avoid subqueries because they degrade processing speed.

MySQL export to CSV

While working through export techniques in MySQL (5.1.34-community), I discovered some tricks and techniques with MySQL exports to a CSV file.

Here’s a standard export statement to a CSV file format:

mysql> SELECT * -> INTO OUTFILE 'C:/Data/City.csv' -> FIELDS TERMINATED BY ',' -> ENCLOSED BY '"' -> ESCAPED BY '\\' -> LINES TERMINATED BY '\r\n' -> FROM City; Query OK, 4079 ROWS affected (0.02 sec) |

On Microsoft Windows, when you attempt to export it a second time, you’ll get an error unless you’ve previously deleted the physical file. You’ll also need the \r on the Windows platform but not the Linux platform.

mysql> SELECT * -> INTO OUTFILE 'C:/Data/City.csv' -> FIELDS TERMINATED BY ',' -> ENCLOSED BY '"' -> ESCAPED BY '\\' -> LINES TERMINATED BY '\r\n' -> FROM City; ERROR 1086 (HY000): File 'c:/Data/City.csv' already EXISTS |

While reviewing Alan Beaulieu’s Learning SQL, 2nd Edition, I noticed he’s got a small example in his Appendix B. He’s using the back-quoted backslash approach to directories in Windows. You can use it, but I prefer the one shown in my examples. Here’s the alternative syntax for the outbound file line:

-> INTO OUTFILE 'C:\\Data\\City.csv' |

When you want to use the CASE statement, you need to use a derived (MySQL terminology). It appears that you can’t include a CASE statement in the SELECT clause when exporting the contents to an OUTFILE. Also, for reference, MySQL doesn’t support the WITH clause.

SELECT * INTO OUTFILE 'c:/Data/City4.csv' FIELDS TERMINATED BY ',' ENCLOSED BY '"' ESCAPED BY '\\' LINES TERMINATED BY '\r\n' FROM (SELECT ID , CASE WHEN Name IS NULL THEN '' ELSE Name END AS Name , CASE WHEN CountryCode IS NULL THEN '' ELSE CountryCode END AS CountryCode , CASE WHEN District IS NULL THEN '' ELSE District END AS District , CASE WHEN Population IS NULL THEN '' ELSE Population END AS Population FROM City) Subquery; |

Hope this helps somebody.

Oracle Interval Data Types

I saw an interesting post on INTERVAL YEAR TO MONTH while checking things out today. It struck me as odd, so I thought I’d share a similar sample along with my opinion about how it should be done in a PL/SQL block.

The example is a modification of what I found in a forum. You should see immediately that it’s a bit complex and doesn’t really describe what you should do with any months. Naturally, the example only dealt with years.

DECLARE lv_interval INTERVAL YEAR TO MONTH; lv_end_day DATE := '30-APR-2009'; lv_start_day DATE := '30-APR-1975'; BEGIN lv_interval := TO_CHAR(FLOOR((lv_end_day - lv_start_day)/365.25))||'-00'; DBMS_OUTPUT.put_line(lv_interval); END; / |

I suggest that the better way is the following because it allows for months, which are a bit irregular when it comes to divisors.

DECLARE lv_interval INTERVAL YEAR TO MONTH; lv_end_day DATE := '30-APR-2009'; lv_start_day DATE := '30-JAN-1976'; BEGIN lv_interval := TO_CHAR(EXTRACT(YEAR FROM lv_end_day) - EXTRACT(YEAR FROM lv_start_day)) ||'-'|| TO_CHAR(EXTRACT(MONTH FROM lv_end_day) - EXTRACT(MONTH FROM lv_start_day)); DBMS_OUTPUT.put_line(lv_interval); END; / |

Let me know if you’ve another alternative that you prefer.

T-SQL Hierarchical Query

Playing around with Microsoft SQL Server 2008 Express edition, I’ve sorted through a bunch of tidbits. One that I thought was interesting, is how to perform a recursive or hierarchical query. This describes how you can perform the magic.

The official name of the WITH clause in Oracle’s lexicon (otherwise known as Oraclese) is a subquery factoring clause. You can find more on that in this earlier blog post. Microsoft has a different name for the WITH clause. They call it a Common Table Expression or CTE.

You perform recursive queries in Microsoft SQL Server 2008 by leveraging CTEs. I’ve modified the setup code from that earlier blog post to run in SQL Server 2008. You’ll find it at the bottom of this blog post.

Unless you want to write your own C# (.NET is the politically correct lingo) equivalent to Oracle’s SQL*Plus, you’ll need to run this script in the SQL Server Management Studio. Actually, you can use Microsoft SQL Server 2008’s command-line utility, which is called sqlcmd.exe but it is much less robust than SQL*Plus. In the Management Studio, you click File, then Open, and File… to load the file for execution, and then click the Execute button. You need to be careful you don’t click the Debug button, which is the green arrow to the right of the Execute button.

![]()

This is the magic query in the illustration. You can also find it in the source code. At the end of the day, I’m hard pressed to understand why they’d use a UNION ALL to support recursion.

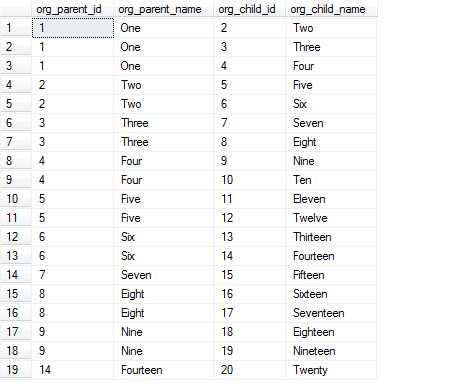

The top-most CTE, or subquery factoring clause, simply joins the ORGANIZATION_NAME to the ORG_PARENT_ID and ORG_CHILD_ID columns to provide a single working source. The second CTE performs the recursion. The top-query sets the starting row, and the second query recursively navigates the tree. After all children are found, the first query moves to the next element in the table and recursively searches for its children.

You should note that the CTE self-references itself from inside the second query. Then, the external query (the non-CTE query) returns the results by querying the same CTE.

This logic behaves more like a nested loop, and actually fails to move down branches of the tree like a recursive program. Otherwise line 19 would be line 14 in the output. You could write another CTE to fix this shortfall, thereby mirroring a true recursive behavior, or you can write a stored procedure.

The illustrated query outputs the following hierarchical relationship, which navigates down the hierarchical tree:

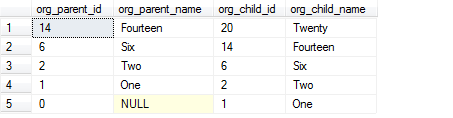

You can also go up any branch of the tree by changing some of the logic. You’ll find the query to navigate up the tree as the second query in the setup script at the end of the blog. It renders the following output:

The blog will be updated if I discover the equivalent to the LEVEL in Oracle’s self-referencing semantics. If you know it, please share it with everybody.

Setup Script

Microsoft SQL Server 2008 Join Script

USE student; BEGIN TRAN; -- Conditionally drop tables when they exist. IF OBJECT_ID('dbo.ORGANIZATION','U') IS NOT NULL DROP TABLE dbo.ORGANIZATION; IF OBJECT_ID('dbo.ORG_STRUCTURE','U') IS NOT NULL DROP TABLE dbo.ORG_STRUCTURE; -- Create the organization table. CREATE TABLE ORGANIZATION ( organization_id INT , organization_name VARCHAR(10)); -- Seed the organizations. INSERT INTO dbo.ORGANIZATION VALUES (1,'One'), (2,'Two'), (3,'Three'), (4,'Four'), (5,'Five') ,(6,'Six'), (7,'Seven'), (8,'Eight'), (9,'Nine'), (10,'Ten') ,(11,'Eleven'), (12,'Twelve'), (13,'Thirteen'), (14,'Fourteen'), (15,'Fifteen') ,(16,'Sixteen'), (17,'Seventeen'), (18,'Eighteen'), (19,'Nineteen'), (20,'Twenty'); -- Create the organization structure table that holds the recursive key. CREATE TABLE org_structure ( org_structure_id INT , org_parent_id INT , org_child_id INT ); -- Seed the organization structures. INSERT INTO org_structure VALUES ( 1, 0, 1),( 1, 1, 2),( 1, 1, 3),( 1, 1, 4),( 1, 2, 5) ,( 1, 2, 6),( 1, 3, 7),( 1, 3, 8),( 1, 4, 9),( 1, 4,10) ,( 1, 5,11),( 1, 5,12),( 1, 6,13),( 1, 6,14),( 1, 7,15) ,( 1, 8,16),( 1, 8,17),( 1, 9,18),( 1, 9,19),( 1,14,20); COMMIT TRAN; -- Navigating down the tree from the root node. WITH org_name AS (SELECT os.org_parent_id AS org_parent_id , o1.organization_name AS org_parent_name , os.org_child_id AS org_child_id , o2.organization_name AS org_child_name FROM dbo.organization o1 RIGHT JOIN dbo.org_structure os ON o1.organization_id = os.org_parent_id RIGHT JOIN dbo.organization o2 ON o2.organization_id = os.org_child_id) , jn AS (SELECT org_parent_id, org_parent_name , org_child_id, org_child_name FROM org_name WHERE org_parent_id = 1 UNION ALL SELECT c.org_parent_id, c.org_parent_name , c.org_child_id, c.org_child_name FROM jn AS p JOIN org_name AS c ON c.org_parent_id = p.org_child_id) SELECT jn.org_parent_id, jn.org_parent_name , jn.org_child_id, jn.org_child_name FROM jn ORDER BY 1; -- Navigating up the tree from the 20th leaf-node child. WITH org_name AS (SELECT os.org_parent_id AS org_parent_id , o1.organization_name AS org_parent_name , os.org_child_id AS org_child_id , o2.organization_name AS org_child_name FROM dbo.organization o1 RIGHT JOIN dbo.org_structure os ON o1.organization_id = os.org_parent_id RIGHT JOIN dbo.organization o2 ON o2.organization_id = os.org_child_id) , jn AS (SELECT org_parent_id, org_parent_name , org_child_id, org_child_name FROM org_name WHERE org_child_id = 20 UNION ALL SELECT c.org_parent_id, c.org_parent_name , c.org_child_id, c.org_child_name FROM jn AS p JOIN org_name AS c ON c.org_child_id = p.org_parent_id) SELECT jn.org_parent_id, jn.org_parent_name , jn.org_child_id, jn.org_child_name FROM jn ORDER BY 1 DESC; |

Object Record Collections

It must have been disgust with learning that a Result Cache function couldn’t use an object type that made me zone on showing how to use an object type as the return type of a PL/SQL table function. The nice thing about this approach, as pointed out by Gary Myer’s comment on another blog post, is that it doesn’t require a pipelined function to translate it from PL/SQL to SQL scope.

The first step is to create an object type without a return type of SELF, which Oracle elected as its equivalent to this for some unknown reason. A user-defined type (UDT) defined without a return type, returns the record structure of the object, but as mentioned it is disallowed in result cache functions. After you define the base type, you create a collection of the base UDT. Then, you can use the UDT as a SQL return type in your code, like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 | CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION get_common_lookup_object_table ( table_name VARCHAR2 , column_name VARCHAR2 ) RETURN common_lookup_object_table IS -- Define a dynamic cursor that takes two formal parameters. CURSOR c (table_name_in VARCHAR2, table_column_name_in VARCHAR2) IS SELECT common_lookup_id , common_lookup_type , common_lookup_meaning FROM common_lookup WHERE common_lookup_table = UPPER(table_name_in) AND common_lookup_column = UPPER(table_column_name_in); -- Declare a counter variable. counter INTEGER := 1; -- Declare a package collection data type as a SQL scope table return type. list COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT_TABLE := common_lookup_object_table(); BEGIN -- Assign the cursor return values to a record collection. FOR i IN c(table_name, column_name) LOOP list.extend; list(counter) := common_lookup_object(i.common_lookup_id ,i.common_lookup_type ,i.common_lookup_meaning); counter := counter + 1; END LOOP; -- Return the record collection. RETURN list; END get_common_lookup_object_table; / |

You can then query it in SQL like this:

COLUMN common_lookup_id FORMAT 9999 HEADING "ID" COLUMN common_lookup_type FORMAT A16 HEADING "Lookup Type" COLUMN common_lookup_meaning FORMAT A30 HEADING "Lookup Meaning" SELECT * FROM TABLE(get_common_lookup_object_table('ITEM','ITEM_TYPE')); |

This depends on the same sample code that I use elsewhere on the blog. You can download it from McGraw-Hill’s web site. You can also find a complete and re-runnable script by clicking on the down arrow below.

Code Script ↓

BEGIN FOR i IN (SELECT object_name , object_type FROM user_objects WHERE object_name = 'GET_COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT_TABLE') LOOP EXECUTE IMMEDIATE 'DROP '||i.object_type||' '||i.object_name; END LOOP; FOR i IN (SELECT type_name FROM user_types WHERE type_name = 'COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT_TABLE') LOOP EXECUTE IMMEDIATE 'DROP TYPE '||i.type_name; END LOOP; FOR i IN (SELECT type_name FROM user_types WHERE type_name = 'COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT') LOOP EXECUTE IMMEDIATE 'DROP TYPE '||i.type_name; END LOOP; END; / CREATE OR REPLACE TYPE common_lookup_object IS OBJECT ( common_lookup_id NUMBER , common_lookup_type VARCHAR2(30) , common_lookup_meaning VARCHAR2(255)); / CREATE OR REPLACE TYPE common_lookup_object_table IS TABLE OF common_lookup_object; / CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION get_common_lookup_object_table ( table_name VARCHAR2 , column_name VARCHAR2 ) RETURN common_lookup_object_table IS -- Define a dynamic cursor that takes two formal parameters. CURSOR c (table_name_in VARCHAR2, table_column_name_in VARCHAR2) IS SELECT common_lookup_id , common_lookup_type , common_lookup_meaning FROM common_lookup WHERE common_lookup_table = UPPER(table_name_in) AND common_lookup_column = UPPER(table_column_name_in); -- Declare a counter variable. counter INTEGER := 1; -- Declare a package collection data type as a SQL scope table return type. list COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT_TABLE := common_lookup_object_table(); BEGIN -- Assign the cursor return values to a record collection. FOR i IN c(table_name, column_name) LOOP list.extend; list(counter) := common_lookup_object(i.common_lookup_id ,i.common_lookup_type ,i.common_lookup_meaning); counter := counter + 1; END LOOP; -- Return the record collection. RETURN list; END get_common_lookup_object_table; / TTITLE OFF COLUMN common_lookup_id FORMAT 9999 HEADING "ID" COLUMN common_lookup_type FORMAT A16 HEADING "Lookup Type" COLUMN common_lookup_meaning FORMAT A30 HEADING "Lookup Meaning" SELECT * FROM TABLE(get_common_lookup_object_table('ITEM','ITEM_TYPE')); |

Describe User Record Types

Gary Myers made a comment on the blog that got me thinking about how to look up user defined types (UDTs). Like those UDTs that you define to leverage pipelined functions and procedures. It became more interesting while considering how Oracle Object Types act as SQL record types. At least, that’s their default behavior when you don’t qualify a return type of self (that’s this in Oracle objects for those who write in any other object-oriented programming language).

The following query creates a view of data types in your user schema. It is fairly straightforward and written to let you deploy the view in any schema. You’ll need to make changes if you’d like it work against the ALL or DBA views.

CREATE OR REPLACE VIEW schema_types AS SELECT ut.type_name AS type_name , uta.attr_no AS position_id , uta.attr_name AS attribute_name , DECODE(uta.attr_type_name , 'BFILE' ,'BINARY FILE LOB' , 'BINARY_FLOAT' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'BINARY_DOUBLE',uta.attr_type_name , 'BLOB' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'CLOB' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'CHAR' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'DATE' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'FLOAT' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'LONG RAW' ,uta.attr_type_name , 'NCHAR' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'NVARCHAR2' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'NUMBER' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.precision||uta.scale,0) , 0,uta.attr_type_name , DECODE(NVL(uta.scale,0),0 , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.precision||')' , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.precision||','|| uta.scale||')')) , 'RAW' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'VARCHAR' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'VARCHAR2' ,DECODE(NVL(uta.length,0),0,uta.attr_type_name , uta.attr_type_name||'('||uta.length||')') , 'TIMESTAMP' , uta.attr_type_name,uta.attr_type_name) AS attr_type_name FROM user_types ut, user_type_attrs uta WHERE ut.type_name = uta.type_name ORDER BY ut.type_name, uta.attr_no; |

You can query and format the view as follows:

CLEAR BREAKS CLEAR COLUMNS CLEAR COMPUTES TTITLE OFF SET ECHO ON SET FEEDBACK OFF SET NULL '' SET PAGESIZE 999 SET PAUSE OFF SET TERM ON SET TIME OFF SET TIMING OFF SET VERIFY OFF ACCEPT INPUT PROMPT "Enter type name: " SET HEADING ON TTITLE LEFT o1 SKIP 1 - '--------------------------------------------------------' SKIP 1 CLEAR COLUMNS CLEAR BREAKS BREAK ON REPORT BREAK ON c1 SKIP PAGE COL c1 NEW_VALUE o1 NOPRINT COL c2 FORMAT 999 HEADING "ID" COL c3 FORMAT A32 HEADING "Attribute Name" COL c4 FORMAT A33 HEADING "Attribute Type" SELECT st.type_name c1 , st.position_id c2 , st.attribute_name c3 , st.attr_type_name c4 FROM schema_types st WHERE st.type_name LIKE UPPER('&input')||'%' ORDER BY st.type_name , st.position_id; |

Here’s a sample output for an object type named common_lookup_object:

COMMON_LOOKUP_OBJECT -------------------------------------------------------- ID Attribute Name Attribute TYPE ---- -------------------------------- ------------------ 1 COMMON_LOOKUP_ID NUMBER 2 COMMON_LOOKUP_TYPE VARCHAR2(30) 3 COMMON_LOOKUP_MEANING VARCHAR2(255) |

It certainly makes the point that a named data type is most convenient. I’m still working through the metadata to find how to link those meaningless type names back to meaningful package specifications. If you know, let me know in a comment. Hope this helps somebody.

Beats a reference cursor

You can’t beat play’n around with the technology. It seems that each time I experiment with something to answer a question, I discover new stuff. So, I really appreciate that Cindy Conlin asked me to net out why a PL/SQL Pipelined Table function existed at UTOUG Training Days 2009.

I found that Java and PHP have a great friend in Pipelined Table functions because when you wrap them, you can simplify your code. While a reference cursor lets you return the product of a bulk operation, it requires two hooks into the database. One for the session connection and another for the connection to the system reference cursor work area. While this was a marvelous feature of the OCI8 library, which I duly noted in my Oracle Database 10g Express Edition PHP Web Programming book, there’s a better way.

The better way is a Pipelined Table function because you can query it like you would a normal table or view. Well, not exactly but the difference involves the TABLE function, and it is really trivial.

When you call a Pipelined Table function, you only need to manage a single hook into the database. That hook is for the session connection. You can find a full (really quite detailed) treatment of Table and Pipelined Table functions in this blog page. Building on that blog page, here’s a simple PHP program that demonstrates the power of leveraging the SQL context provided by a Pipelined Table function.

<?php // Connect to the database. if ($c = @oci_connect("plsql","plsql","orcl")) { // Parse a query to a resource statement. $s = oci_parse($c,"SELECT * FROM TABLE(get_common_lookup_plsql_table('ITEM','ITEM_TYPE'))"); // Execute query without an implicit commit. oci_execute($s,OCI_DEFAULT); // Open the HTML table. print '<table border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="3">'; // Read fetched headers. print '<tr>'; for ($i = 1;$i <= oci_num_fields($s);$i++) print '<td class="e">'.oci_field_name($s,$i).'</td>'; print '</tr>'; // Read fetched data. while (oci_fetch($s)) { // Print open and close HTML row tags and columns data. print '<tr>'; for ($i = 1;$i <= oci_num_fields($s);$i++) print '<td class="v">'.oci_result($s,$i).'</td>'; print '</tr>'; } // Close the HTML table. print '</table>'; // Disconnect from database. oci_close($c); } else { // Assign the OCI error and format double and single quotes. $errorMessage = oci_error(); print htmlentities($errorMessage['message'])."<br />"; } ?> |

You’ll notice that all the information that is expected from a query against a table or view is also available from the result of Pipelined Table function. That’s because the Pipeline Table function actually places the internal record structure of a PL/SQL collection into the SQL context along with the data.

This sample PHP program produces the following XHTML output:

| COMMON_LOOKUP_ID | COMMON_LOOKUP_TYPE | COMMON_LOOKUP_MEANING |

| 1013 | DVD_FULL_SCREEN | DVD: Full Screen |

| 1014 | DVD_WIDE_SCREEN | DVD: Wide Screen |

| 1015 | GAMECUBE | Nintendo GameCube |

| 1016 | PLAYSTATION2 | PlayStation2 |

| 1019 | VHS_DOUBLE_TAPE | VHS: Double Tape |

| 1018 | VHS_SINGLE_TAPE | VHS: Single Tape |

| 1017 | XBOX | XBOX |

Naturally, you can parameterize your PHP program and add bind variables to make this more dynamic. An example of parameterizing the call to a Pipelined Function is provided in the next program example.

You would use the following URL to call the dynamic PHP program:

http://mclaughlin11g/GetCommonLookup.php?table=ITEM&column=ITEM_TYPE |

The working PHP program code is:

<?php // Declare input variables. (isset($_GET['table'])) ? $table = $_GET['table'] : $table = "ITEM"; (isset($_GET['column'])) ? $column = $_GET['column'] : $column = 'ITEM_TYPE'; // Connect to the database. if ($c = @oci_connect("plsql","plsql","orcl")) { // Parse a query to a resource statement. // Don't use table and column because they're undocumented reserved words in the OCI8. $s = oci_parse($c,"SELECT * FROM TABLE(get_common_lookup_plsql_table(:itable,:icolumn))"); // Bind a variable into the resource statement. oci_bind_by_name($s,":itable",$table,-1,SQLT_CHR); oci_bind_by_name($s,":icolumn",$column,-1,SQLT_CHR); // Execute query without an implicit commit. oci_execute($s,OCI_DEFAULT); // Open the HTML table. print '<table border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="3">'; // Read fetched headers. print '<tr>'; for ($i = 1;$i <= oci_num_fields($s);$i++) print '<td class="e">'.oci_field_name($s,$i).'</td>'; print '</tr>'; // Read fetched data. while (oci_fetch($s)) { // Print open and close HTML row tags and columns data. print '<tr>'; for ($i = 1;$i <= oci_num_fields($s);$i++) print '<td class="v">'.oci_result($s,$i).'</td>'; print '</tr>'; } // Close the HTML table. print '</table>'; // Disconnect from database. oci_close($c); } else { // Assign the OCI error and format double and single quotes. $errorMessage = oci_error(); print htmlentities($errorMessage['message'])."<br />"; } ?> |

You may note that the parameter values (placeholders or bind variables inside the SQL statement) are prefaced with an i. That’s because TABLE and COLUMN are restricted key words in the context of OCI8, and their use triggers an ORA-01036 exception.

This makes PHP more independent of the OCI8 library and easy to cross port to other databases if that’s a requirement. Hope this helps some folks.

Pipelined function update

When I presented the concept at the Utah Oracle User’s Group (UTOUG) Training Days 3/12-3/13/2009 it became clear the community could benefit from more detail about table and pipelined table functions. The question asked was: “What’s the primary purpose for pipelined table functions?”

My answer is: The primary purpose of a pipelined table function lets you retrieve PL/SQL record collection structures in a SQL context.

If there’s another reason that I missed, please let me know. It took a couple days to expand the older post to be more complete.

Colons are PL/SQL gnats

Today, one of my students made a common error working in a PL/SQL programming unit. The stumped student called the tutor over, and then the tutor called me over. The tutor asked me how the DBMS_OUTPUT package could be out of scope. When I saw the SP2-0552 error, it was straightforward to remove a stray colon, but I realized that recognizing the colon as an error wasn’t straightforward.

The error picks the string that follows a colon inside a program unit. This behavior is the same regardless of whether the colon is found in the declaration, execution, or exception block. Most likely, the string is the beginning of the next line because the colon is most frequently a mistyped semicolon.

SP2-0552: Bind variable "DBMS_OUTPUT" NOT declared. |

The easiest way to find it is not to look for the string but simply for a colon with the find feature of the editor. Then, you must either replace it or give it a valid bind variable name. You define bind variables in the SQL*Plus environment with the VARIABLE keyword.

You may also be interested in how to put a colon inside an NDS statement. If so, you can check this blog post.

SQL Concatenation blues

I really like Alan Beaulieu’s Learning SQL because its simple, direct, and clearer than other books on SQL. While his focus is MySQL, he does a fair job of injecting a bit about Oracle’s syntax. Comparative concatenation syntax is one of topics I wished he’d spent more time on. Here’s some clarification on cross platform SQL concatenation.

Oracle

Oracle supports two forms of string concatenation. Concatenation for those new to the idea means gluing two strings into one, or three strings into one, et cetera. One uses the || operator, which looks like two pipes. You can use the || operator between any number of string elements to glue them together. A quick example of the || operator that returns an ABCD string is:

SELECT 'A' || 'B' || 'C' || 'D' FROM dual; |

The Oracle database also supports the CONCAT operator that many use in MySQL. Those converting to an Oracle database should beware the difference between how the CONCAT function is implemented in Oracle versus MySQL. In an Oracle database, the CONCAT function only takes two arguments. When you call it with three or more arguments like this:

SELECT CONCAT('A','B','C','D') FROM dual; |

It raises the following exception:

SELECT CONCAT('A','B','C','D') FROM dual * ERROR at line 1: ORA-00909: invalid NUMBER OF arguments |

You can use the CONCAT function to process more than two arguments but you must do so by calling the function recursively. You’d do it like this if you must use it:

SELECT CONCAT('A',CONCAT('B',CONCAT('C','D'))) FROM dual; |

As to an Oracle specific SQL book recommendation, I’d go with Alan’s as a beginner even though it’s focus is MySQL. By the way, if you don’t own Learning SQL hold off on buying it until the second edition is available in May 2009. If you’re using Oracle and have some basic SQL competence, I’d suggest Mastering Oracle SQL, 2nd Edition

by Sanjay Mishra and Alan Beaulieu as a reference. Just make sure you get the 2nd Edition of it too.

MySQL

MySQL appears to support the two same forms of string concatenation as an Oracle database. The one that uses the || operator (known as pipe concatenation), actually only returns a zero unless you configure the sql_mode to allow pipe concatenation.

The following concatenation statement uses pipe concatenation:

mysql> SELECT 'A'||'B'||'C'||'D'; +--------------------+ | 'A'||'B'||'C'||'D' | +--------------------+ | 0 | +--------------------+ 1 ROW IN SET, 4 warnings (0.00 sec) |

By default, this fails and returns a zero unless you’ve added the PIPES_AS_CONCAT mode to your sql_mode variable. It returns a zero because it attempts to see whether either of the adjoining elements are true. Strings inherently fail to resolve as expressions or Boolean values and the function returns a zero, which means the composite expression was evaluated as false.

You can query the sql_mode variable as follows. The default values are shown in the results.

mysql> SELECT @@sql_mode; +----------------------------------------------------------------+ | @@sql_mode | +----------------------------------------------------------------+ | STRICT_TRANS_TABLES,NO_AUTO_CREATE_USER,NO_ENGINE_SUBSTITUTION | +----------------------------------------------------------------+ 1 ROW IN SET (0.00 sec) |

You can modify the sql_mode as follows from the command line:

SET sql_mode='STRICT_TRANS_TABLES,NO_AUTO_CREATE_USER,NO_ENGINE_SUBSTITUTION,PIPES_AS_CONCAT'; |

If you want to make this a permanent change, you can edit the my.ini file in Windows or the my.conf file in Unix or Linux. The following shows the modified line in a configuration file.

# Set the SQL mode to strict sql-mode="STRICT_TRANS_TABLES,NO_AUTO_CREATE_USER,NO_ENGINE_SUBSTITUTION,PIPES_AS_CONCAT" |

With these changes pipe concatenation works in MySQL, as follows:

mysql> SELECT 'A'||'B'||'C'||'D'; +--------------------+ | 'A'||'B'||'C'||'D' | +--------------------+ | ABCD | +--------------------+ 1 ROW IN SET (0.02 sec) |

You can use the CONCAT function to glue any number of string elements together when you’ve no control of the sql_mode variable. The CONCAT function in MySQL takes several arguments. I’ve never needed to use more than the limit and suspect that there isn’t one (based on the documentation). It appears to use a recursive algorithm for parameter processing. Please post a note correcting me if I’m wrong on this.

You call the CONCAT function like this:

SELECT CONCAT('A','B','C','D'); |

As to a MySQL specific SQL book recommendation, I’d go with Alan Beaulieu’s Learning SQL as a beginner. As noted earlier, don’t buy it until the 2nd Edition ships in May 2009.

Microsoft® Access or SQL Server

Microsoft® SQL Server doesn’t support two forms of string concatenation like Oracle and MySQL. You can only use the + operator. There is no CONCAT function in Microsoft® Access or SQL Server. A quick example of the + operator in Microsoft’s SQL returns an ABCD string like this:

SELECT 'A' + 'B' + 'C' + 'D'; |

As to a Microsoft® T-SQL book recommendation, I’d go with Itzik Ben-Gan’s Microsoft SQL Server 2008 T-SQL Fundamentals. Just understand, that like most things Microsoft, T-SQL is a dialect and approach that differs substantially from other commercial products.