SELECT Statement

SQL Statement Behavior

Learning Outcomes

- Learn how to write

SELECTstatements. - Learn how SQL executes

SELECTclauses. - Learn how

SELECTstatements can work independently or as subqueries.

Lesson Materials

The SELECT statement in SQL lets you query data. The designers of SQL felt the best programming languages would be ones that mirrored natural language. Therefore, the SELECT statement reads as an English sentence but underneath the syntax it runs in a traditional logical order of operation.

Each keyword in a SELECT statement is a clause. The clauses of a SELECT statement are the:

SELECTclause orSELECT-list qualifies the columns returned by a query.FROMclause qualifies the table sources for a query and any table aliases.WHEREclause filters the pre-aggregated rows of the result set.GROUP BYclause identifies the column or set of columns that determines how values are aggregated (a fancy word for adding, averaging, counting, or calculating a value).HAVINGclause filters the aggregated rows of the result set.ORDER BYclause sorts the rows returned by the query.

The general prototype of a SELECT statement from a single table or pseudo table is:

SELECT expression [, expression [, ... ]] FROM {table_name | pseudo_table_name} [table_alias] [WHERE predicate [AND predicate [OR predicate [{AND|OR} ...]]]] [GROUP BY expression [, expression]] [HAVING predicate] [ORDER BY {expression | SELECT-list_column_position [ASC | DESC] [, {expression | SELECT-list_column_position [ASC | DESC]]; |

The SQL specification labels expressions as numeric literal, string literal, computation, and concatenation values. Comparisons in the WHERE and HAVING clauses are predicates in the SQL specification.

The general prototype of a SELECT statement from a single table or pseudo table is:

SELECT {numeric_literal | string_literal | column_name | computation | concatenation} [, {numeric_literal | string_literal | column_name | computation | concatenation} [, ... ]] FROM {table_name | pseudo_table_name} [table_alias] [WHERE {column_name = {numeric_literal | string_literal | computation | concatenation} [AND {column_name = {numeric_literal | string_literal | computation | concatenation} [OR {column_name = {numeric_literal | string_literal | computation | concatenation} [{AND|OR} ...]]]] [GROUP BY {column_name | computation | concatenation} [, {column_name | computation | concatenation}]] [HAVING {aggregation_value [= | >= | <=] {numeric_literal | computation}] [ORDER BY {column_name | SELECT-list_column_position [ASC | DESC]]; |

The SQL specification labels expressions as numeric literal, string literal, computation, and concatenation values. Comparisons in the WHERE and HAVING clauses are predicates in the SQL specification.

The FROM clause above only holds one table but the FROM clause can hold a comma-delimited series of table or pseudo table names in ANSI 1989 style. The FROM clause can hold much more in ANSI 1992 style, such as the table names and join conditions. Multiple table FROM clauses are covered later after you’ve mastered single table SELECT statements.

The equal (=) symbol in the WHERE clause is a simplification to illustrate a general prototype. You can replace the equal symbol with a number of different comparison operators, which are covered in the WHERE Clause page on this website.

A value comparison operator may evaluate the content of the left column or literal value to see if it holds the same values as the right column or literal value. Alternatively, a comparison operator may evaluate the content of a left column or literal value to see if it holds the same values as a list of values in the right column. A list of values in this case may be a comma delimited list inside parentheses or the result set of an embedded SELECT statement, which is also known as a subquery.

While comparing values may seem simple to us as humans, it isn’t simple to computers. Before the value comparison operator can check whether the values are equal it must first ensure the left and right values (known as operands) have the same data type. If they don’t have the same data type, the database must cast one of them to the other data type before it can compare their values.

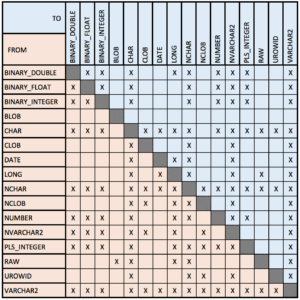

While data types are basically numbers, strings, and dates, there are a number of rules that govern them. Each database has rules that govern how a programmer can convert values to explicitly cast data types, but the Oracle database can implicitly cast between the following data types:

The execution order of the clauses in a SELECT statement differ in various scenarios. The scenarios and their execution orders are:

- A query with a

SELECT-list andFROMclause; and they run in the following order:- The

FROMclause finds the table or tables. - The

SELECT-list returns the column or columns from a table or tables.

- The

- A query with a

SELECT-list,FROMclause, andWHEREclause:- The

FROMclause finds the table or tables. - The

WHEREclause filters the rows returned by the table or tables. - The

SELECT-list returns the column or columns from a table or tables.

- The

- A query with a

SELECT-list,FROMclause,WHEREclause, andORDER BYclause:- The

FROMclause finds the table or tables. - The

WHEREclause filters the rows returned by the table or tables. - The

ORDER BYclause sorts the rows returned by the query. - The

SELECT-list returns the column or columns from a table or tables.

- The

- A query with a

SELECT-list,FROMclause,WHEREclause,ORDER BYclause, andGROUP BYclause:- The

FROMclause finds the table or tables. - The

WHEREclause filters the rows returned by the table or tables. - The

GROUP BYclause aggregates the rows by identifying the column or set of columns that determines how values are aggregated. - The

ORDER BYclause sorts the rows returned by the query. - The

SELECT-list returns the column or columns from a table or tables.

- The

- A query with a

SELECT-list,FROMclause,WHEREclause,ORDER BYclause,GROUP BYclause, andHAVINGclause:- The

FROMclause finds the table or tables. - The

WHEREclause filters the rows returned by the table or tables. - The

GROUP BYclause aggregates the rows by identifying the column or set of columns that determines how values are aggregated. HAVINGclause filters the aggregated rows of the result set.- The

ORDER BYclause sorts the rows returned by the query. - The

SELECT-list returns the column or columns from a table or tables.

- The

SELECT statements may run as standalone statements or they may run as subordinate parts of other SELECT statements. You may also write SELECT statements inside INSERT, UPDATE, MERGE, and DELETE statements. You label a SELECT statement as a subquery when you put it inside another statement.

There are four types of subqueries:

- A scalar subquery returns only one column and one row.

- A single-row subquery returns one row with two or more columns.

- A multiple-row subquery returns two or more rows with two or more columns.

- A correlated subquery includes a join between the subquery and the outer statement but returns no values to outer statement.

The behaviors of the individual clauses are described in their respective web pages. You also have the ability to embed a subquery in the FROM clause. An embedded query in the FROM clause treats the result set of the query as a dynamic table. ANSI 1999 SQL introduces the WITH clause as an alternative to putting subqueries in the FROM clause.

A WITH clause runs before the rest of the query and it is a list of comma-delimited named SELECT statements. Each named SELECT statement is also known as a Common Table Expression (CTE) because it returns a result set. A WITH clause also precedes the primary SELECT statement. Each of the

The first SELECT statement in a WITH clause runs in isolation from any other SELECT statements in the comma-delimited list of named SELECT statements. All subsequent SELECT statements in list of named SELECT statements can refer to any of the previously named SELECT statements. The primary SELECT statement can reference all of the named SELECT statements in the WITH clause.

Below is the general prototype of a SELECT statement with a WITH clause. Each SELECT statement in the comma-delimited set may:

- Have any of the normal clauses defined in the general prototype of a

SELECTstatement or query. - Reference one or more tables not that may be unrelated to the base table or tables of the

SELECTstatement. TheSELECTstatement may reference all result set name values from the comma-delimited list in theWITHclause.

WITH result_set_name AS (SELECT statement) [, result_set_name AS (SELECT statement) SELECT statement; |

The named SELECT statements or CTEs inside the WITH clause return their results into memory. You can access the CTE values in multiple scopes within the primary SELECT statement. This ability replaces the older solution. The older solution was quite ineffective because it required you to write the same query as subqueries in multiple places and each copy ran independently in their respective scope.

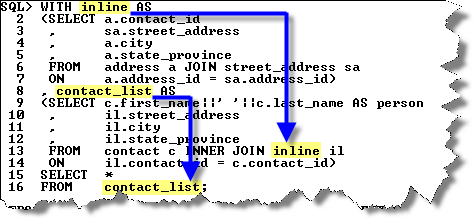

The following image shows you a WITH clause with two comma-delimited named SELECT statements. The first named subquery is inline and the second named subquery is contact_list; and the results are joined together on line 13 of the contact_list named subquery. The primary SELECT statement returns the unfiltered result set from the join of the two named subqueries. You should note that this is effectively a multiple-row subquery, which can only be accessed in two contexts: inside the FROM clause as a CTE (or, run-time view) and as right operand of a lookup operator (IN, =ANY, =SOME, =AND).

Subsequent web pages will demonstrate how to write subqueries and demonstrate how the WITH clause works with scalar, single-row, and correlated subqueries. They will also explain the concept of joining two or more tables together.